Collective#

Overview#

A collective effects element can be added to any lattice to model impedance driven collective effects and perform multi-particle tracking. This element can be constructed with either a user defined table, or by using the built in functions to construct specific elements (for example a longitudinal resonator or a transverse resistive wall). The element will then call the WakeFieldPass PassMethod.

The wake field is applied by first uniformly slicing the full region occupied by the particles in the ct co-ordinate. Each particle is attributed to a given slice, which is represented by a weight. The mean position in x,y,ct is computed for each slice. The kick from one slice to the next (and the self kick for some cases) can then be computed by taking into account the differences in offsets of each slice. This total kick is computed and the appropriate modification to x’, y’ or dp is applied to each particle.

To take into account multi-turn wakes, the wake element has a TurnHistory buffer. Each turn, the mean x,y,ct and weight of each slice is recorded. At each turn, the array of ct values is increased by one circumference (to take into account the decay between turns). When the kick is computed, the full history of turns to ensure the total kick from all previous turns is considered.

The package is organised as follows:

at.collective.wake_functions contains the analytic wake functions that can be called by the other classes

The longitudinal resonator wake function is given by [1]

where \(R_{s}\) is the resonator shunt impedance in Ohms, \(\alpha=\omega_{R}/2Q\), \(\omega_{R}\) is the resonator angular frequency in Hz.rad, \(Q\) is the resonator quality factor and \(\bar{\omega}=\sqrt{\omega_{R}^{2} - \alpha^{2}}\) . The units of the longitudinal wake function are V/C.

The transverse resonator wake function is given by [2]

Here we use the slightly modified transverse resonator function in the correct AT units that is given by.

The definitions are the same as for the longitudinal resonator.

The units of the transverse resonator wake function are V/C/m

The transverse resistive wall wake function is defined as [3]

Here we use the modified version in the correct AT units given by

where \(b\) is the vacuum chamber half gap in m, \(Z_{0}=\pi * 119.9169832\) is the impedance of free space in Ohms, c is the velocity of light in m/s, \(L\) is the length of resistive wall component and \(\sigma_{c}\) is the conductivity in Siemens.

The transverse resistive wall function is an approximation, as it clearly diverges for \(\tau\) close to 0, but when considering multi bunch models the approximation works well.

Also included is a function to convolve a wake field with a gaussian bunch to compute the wake potential (convolve_wake_fun) This function can be useful to combine multiple wake potentials (for example to include an analytical wake function with the wake potential output from GDfidL).

These above functions can be directly called

from at.collective.wake_functions import long_resonator_wf

from at.collective.wake_functions import transverse_resonator_wf

from at.collective.wake_functions import transverse_reswall_wf

at.collective.wake_objects is used to construct a python object which represents a wake field or wake potential. The functions in wake_objects can be called directly to construct and test (and use for purposes outside of tracking in PyAT). The wake object can contain wake fields in multiple planes simultaneously, and may combine wake fields from a table of data with analytical wake functions. All of this is handled by the functions found in this module.

at.collective.wake_elements uses the functions found in at.collective.wake_objects to generate a wake field element that can be appended to the AT lattice to be used for tracking.

at.collective.haissinski contains functions and methods to solve the Haissinski equation in the presence of a longitudinal wake potential in order to obtain the analytical bunch distribution.

Generating a Wake Element#

We can start with a simple ring.

import at

ring = at.load_m('at/machine_data/esrf.m')

First we can call the fast_ring function to reduce significantly the number of elements we will need to track

fring, _ = at.fast_ring(ring)

We must define an srange for the wake function. The wake_function will be computed at the values of the srange array, and an interpolation will be made during the tracking if the required dz of the 2 slices falls in between 2 data points. As a way of saving memory, the wake_object contains a function for computing the srange such that is is finely sampled only around where the bunches are expected to be. We must also specify how many turns we would like the wake memory to be

from at.constants import clight

from at.collective import Wake

wturns = 50

srange_start = 0

srange_short_end = clight / (2 * ring.get_rf_frequency()) # One half of the bucket width

sample_fine = 1e-5

sample_between_bunches = 1e-2

bunch_spacing = ring.circumference

srange_end = wturns * ring.circumference

srange = Wake.build_srange(srange_start, srange_short_end, sample_fine, sample_between_bunches, bunch_spacing, srange_end)

Now we can define a longitudinal resonator by calling the LongResonatorElement function from wake_elements. First we need to define some resonator parameters

from at.collective.wake_elements import LongResonatorElement

current = 0.1 # A

ring.beam_current = current

f_resonator = ring.get_rf_frequency() - 5e4

qfactor = 4500

rshunt = 6e6

Nslice = 1

welem = LongResonatorElement('LongitudinalResonator', ring, srange, f_resonator, qfactor, rshunt, Nturns=wturns, Nslice=Nslice)

Finally we can append this to the fast ring

fring.append(welem)

Using a Wake Table#

A wake function or wake potential can also be provided from a user defined data or a file. Here we can generate a fake data table using the long_resonator_wf function from at.collective.wake_functions, then we can use it to create a wake element

import numpy

from at.collective import long_resonator_wf

from at.collective.wake_object import WakeType

from at.collective.wake_object import WakeComponent

from at.collective.wake_elements import WakeElement

wf_data = long_resonator_wf(srange, f_resonator, qfactor, rshunt, beta=1)

wa = Wake(srange)

wa.add(WakeType.TABLE, WakeComponent.Z, srange, wf_data)

welem = WakeElement('wake', ring, wa, Nslice=Nslice)

The WakeComponent is used to clearly specify which wake component is being considered. Possible values are Z, DX, DY, QX or QY. The WakeType is used to to clearly specify what type of input the add function can expect. Possible values are FILE, RESONATOR, RESWALL or TABLE.

Using a Wake File#

A wake element can also be generated from file. Arguments can be parsed to the add function to describe clearly which columns of the file refer to which parameter. The columns can also be scaled in order to easily sum multiple files or wake contributions.

wa = Wake(srange)

wake_filename = 'filename.txt'

wa.add(WakeType.FILE, WakeComponent.Z, wake_filename, scol=0, wcol=5, wfact=-1e12)

welem = WakeElement('wake', ring, wa, Nslice=Nslice)

Multiple combinations can all be added to one wake element to bring all wake contributions into one wake element

wa = Wake(srange)

wake_filename_z1 = 'filename_z1.txt'

wf_data_z2 = long_resonator_wf(srange, f_resonator, qfactor, rshunt, beta=1)

wake_filename_dx = 'filename_dx.txt'

wake_filename_dy = 'filename_dy.txt'

wa.add(WakeType.FILE, WakeComponent.Z, wake_filename_z1, scol=0, wcol=5, wfact=-1e12)

wa.add(WakeType.TABLE, WakeComponent.Z, srange, wf_data_z2)

wa.add(WakeType.FILE, WakeComponent.DX, wake_filename_dx, scol=0, wcol=1, wfact=1)

wa.add(WakeType.FILE, WakeComponent.DY, wake_filename_dy, scol=0, wcol=2, wfact=1)

welem = WakeElement('wake', ring, wa, Nslice=Nslice)

Using the Haissinski Class#

NOTE: This module is due for a re-write and a clean up. But the fundamental process will remain the same.

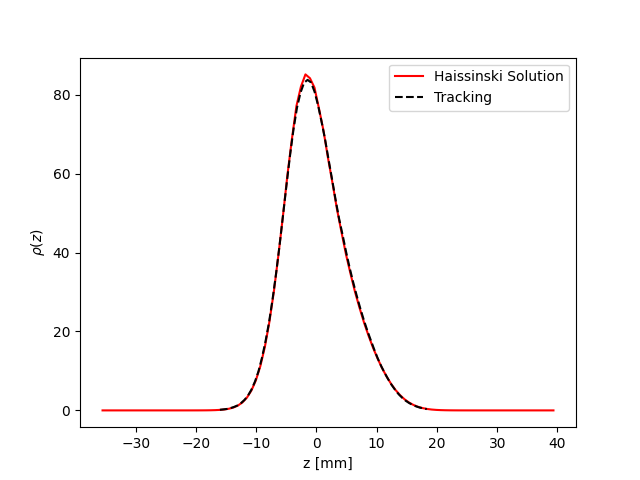

The Haissinski solver is used to compute the equilibrium beam distribution in the presence of a longitudinal impedance. This class is based entirely on the very nice paper by K. Bane and R. Warnock [4]. In this small overview, we will only talk about how to use it. The details can be seen in the paper of exactly how it is implemented. All the functions within the class are cross referenced with the equations found in the paper. An example file which compares the results of tracking and the results of the Haissinski solver can be found in at/pyat/examples/CollectiveEffects/LongDistribution.py.

First we initialise a broadband longitudinal resonator wake function in a wake object.

from at.collective.wake_object import Wake

circ = 843.977

freq = 10e9

qfactor = 1

Rs = 1e4

current = 5e-4

srange = Wake.build_srange(-0.36, 0.36, 1.0e-5, 1.0e-2, circ, circ)

wobj = Wake.long_resonator(srange, freq, qfactor, rshunt, beta = 1)

Now we need to load and run the Haissinski module. The main parameters here are \(m\) which defines the number of steps in the distribution, and \(k_{max}\) which defines the maximum and minimum of the distribution in units of \(\sigma_{z}\). numIters is for the number of iterations for the solver to converge to within a convergence criteria of eps.

from at.collective.haissinski import Haissinski

m = 50 # 30 is quite coarse, 70 or 80 is very fine. 50 is middle

kmax = 8

ha = Haissinski(wobj, ring, m=m, kmax=kmax, current=current, numIters = 30, eps=1e-13)

ha.solve()

The code will now iteratively solve the haissinski equation to determine the beam equilibrium distribution, and will stop running when the distribution no longer changes. Now we can unpack the results and recover some sensible units.

# The x units in the paper are normalised to sigma. So we remove this normalisation.

ha_x_tmp = ha.q_array*ha.sigma_l

# we remove the factor of normalised current

ha_prof = ha.res/ha.Ic

# and now we normalise the profile so the integral is equal to 1

ha_prof /= numpy.trapz(ha_prof, x=ha_x_tmp)

# now we determine the charge center

ha_cc = numpy.average(ha_x_tmp, weights=ha_prof)

# and shift the x position so the bunch is centered around 0

ha_x = (ha_x_tmp - ha_cc)

Multi Bunch Collective Effects#

All pass methods are set to work for multi bunch collective effects with very few modifications. First, the filling pattern must be set

Nbunches = 992

ring.beam_current = 200e-3 #Set total beam current to 200mA

ring.set_fillpattern(Nbunches) #Set uniform filling. Here the harmonic number is equal to 992.

The number of particles in the beam, must be an integer harmonic of the number of bunches. This is because in the pass method, the coordinates are accessed according to \(parts[bunch_id::Nbunches]\). This means all particles for all bunches are in series, and to access the particles for the nth bunch, you simply start at particle n, and take the particle at every Nbunches step. In PyAT we are able to do single slice per bunch, and 1 particle per bunch. Particles can be generated using the standard at.beam functionality.

Two examples of multi bunch collective effects can be found, one for the Longitudinal Coupled Bunch Instability: at/pyat/examples/CollectiveEffects/LCBI_run.py and at/pyat/examples/CollectiveEffects/LCBI_analyse.py, and another for the Transverse Resistive Wall Instability: at/pyat/examples/CollectiveEffects/TRW_run.py and at/pyat/examples/CollectiveEffects/TRW_analyse.py.

Parallelisation with Collective Effects#

PyAT can be run across multiple cores. When using MPI, the user must remember that each thread will be running exactly the same file. This must be taken into account when writing the script. At the beginning of the script, it must have

from mpi4py import MPI

comm = MPI.COMM_WORLD

size = comm.Get_size()

rank = comm.Get_rank()

size is an integer that says how many threads have been created, and rank says which thread you are on. Typically, there are many operations (saving of files, collating of particle data, etc) that you only want to happen on one thread, not on all. So therefore a common trick is to use

rank0 = True if rank == 0

then all of these types of operation can be hidden within an if statement.

if rank0:

# Retrieve some beam data from all threads

# Compute some values to be saved

As mentioned above, the number of particles must be an integer multiple of the number of bunches. When parallelising, this is true of each thread. So if you have 40 threads and 992 bunches, each thread must have an integer multiple of 992 as the number of particles. Otherwise, some particles will be missing and the results will be incorrect. This means that it is not possible to parallelise a computation with 1 particle per bunch. In order to access turn by turn and bunch by bunch data, the beam monitor can be used

bm_elem = at.BeamMoments('monitor')

ring.append(bm_elem)

This monitor works in parallel computations, and the data can be accessed by \(bm_elem.means\) and \(bm_elem.stds\). If the user wishes to write their own data collation, in order to perform some more advanced analysis, functionalities within the MPI4PY package can be used. For example, to compute yourself the centroid position of each bunch in one turn

def compute_centroid_per_bunch(parts, comm, size, Nparts, Nbunches):

all_centroid = numpy.zeros((6, Nbunches))

for i in numpy.arange(Nbunches):

all_centroid[:, i] += numpy.sum(parts[:,i::Nbunches],axis=1)

centroid = comm.allreduce(all_centroid, op=MPI.SUM)/Nparts/size

comm.Barrier()

return centroid

Each thread passes the particles it has to this function. Through the \(comm\) object, the threads can communicate. The sum of each plane is computed, and this sum information is transmitted. Then by dividing with size and Nparts, the mean is computed. The comm.Barrier() functions blocks all threads until they have all reached this point.

A final note of importants, when parallelising, Nslice refers to the number of slices per bunch. The total number of slices used in the computation will there be Nslice*Nbunches

Beam Loading#

An IPAC paper that covers the theory used for the beam loading module can be found in [5].

In order to compensate for the beam induced voltage (which is an additional voltage in the RF cavity arising from the cavity impedance), the cavity voltage (generator voltage \(V_{g}\)) and the cavity frequency (called detuning \(\psi\)) are modified in order to fulfill the cavity setpoints i.e. \(\tilde{V}_{c}=\tilde{V}_{g}+\tilde{V}_{b}\).

To consider beam loading in an rf cavity, a loaded shunt impedance \(R_{s}\) and a loaded quality factor \(Q_{L}\) must be provided. The phasor model is used to compute the amplitude and phase of the beam induced voltage \(V_{b}\). The amplitude and phase are first initialised by computing the optimum detuning \(\psi\) according to the formula found in [5]. From this detuning, the \(V_{g}\) can be easily computed. This is done in the function _init_bl_params found in beam_loading.py.

An important thing to consider for the functions found in the BeamLoadingCavityPass.c and all related functions is the slightly different definition compared to other codes like mbtrack. In PyAT, the RF cavity definition is \(V_{rf}=-sin(k*(z-z_{lag}))\) as opposed to \(V_{rf}=cos(k*(z-z_{lag}))\). This means that when computing the real and imaginary parts of the beam induced voltage from the amplitude and phase of \(V_{b}\), the following conversion must be used:

By default, for a single RF system, the cavity will restore the energy loss per \(U_{0}\) at \(\phi_{s}=-arcsin(U_{0}/V_{rf})\) and the beam will oscillate around ts (the ct coordinate associated to \(\phi_{s}\)). It is possible to change the reference of the time coordinate using the attribute TimeLag from the cavity. For example setting this TimeLag to ts will shift the origin back to zero. In the beamloading element the equilibrium ct coordinate is automatically calculated and the feedback loops will adjust the voltage and phase of the RF wave such that the energy loss due to synchrotron radiation is restored at the equilibrium ct coordinate calculated with the function get_timelag_fromU0.

The phasor model is updated with each slice. At the end of each bucket (filled or empty) the beam induced voltage is back tracked to the expected beam location in the bucket (\(t=ts/clight\) for that bucket). This is why the ts is important, as it allows the feedback to ensure the cavity setpoints are fulfilled at the expected beam position. The final value of \(V_{b}\) at the end of the turn is the mean of all the beam induced voltage from all buckets, measured at \(t=0\) after the bunch has been tracked. The \(V_{b}\) used for the compuation of the \(V_{g}\) can either be taken from the most recent turn, or it can be the mean of a buffer of a specified length.

There are 4 main parameters stored in the beam loading element under the BeamLoadingElement.Vgen. These parameters are \([V_{gen}, \theta_{g}, \psi, V_{gr}]\), where \(V_{gen}\) is the amplitude of the generator voltage, \(\theta_{g}\) is the total generator phase and is typically equal to \(\theta_{g}=\phi_{s}+\psi\), \(\psi\) is the cavity detuning, and \(V_{gr}=V_{gen}/cos(\psi)\) is the generator voltage on resonance.

The computation of the new \(V_{gen}\) is very straight forward. First, the total cavity voltage is computed from the real part of \(V_{b}\) as \(V_{c,meas}=V_{gen}+V_{b}\). Then the correction is computed with \(V_{gr}*={\frac{V_{c,set}}{V_{c,meas}}}^{VoltGain}\). Rather than applying the modification to \(V_{gen}\), it is preferable to apply it by modfying the \(V_{gr}\) as it is independant of the cavity phase.

The phase is slightly more complicated and requires two steps. First to compute to the new detuning, the contribution of the detuning to the total phase shift is extracted with \(\psi += (\theta_{g} - \psi - \phi_{s,set})*PhaseGain\).

This detuning change induces a phase shift which must also be compensated. So the new synchronous phase is computed with the measured real and imaginary cavity voltages \(\theta_{g} -= (-arctan2(V_{c,real}/V_{c,imag}))*PhaseGain\).

Then finally \(V_{gen}\) is updated by \(V_{gen}=V_{gr}cos(\psi)\).

To intialise the beam loading element, the function add_beamloading must be applied to a lattice object. This will convert the specified Cavity Element to a BeamLoadingElement. This can be done as follows

from at.collective import add_beamloading

add_beamloading(ring, qfactor, rshunt,

cavpts=[0], Nslice=1,

VoltGain=0.01, PhaseGain=0.01)

An additional keyword argument cavpts can be given to specifically transfer one cavity element to a beam loading element. The VoltGain and PhaseGain are parameters to be tuned for the feedback.

The dynamics of the simulation are very sensitive to the VoltGain and PhaseGain parameters. Too strong gains can drive oscillations, too weak gains may appear stable but the setpoint criteria are not fulfilled. Be sure to understand the effect of these parameters on your dynamical system!

Several example files can be found in at/pyat/examples/CollectiveEffects that can get any user started quickly.